Doing the work – my recovery from respectful racism

I’ve seen some things the last few months.

I’ve seen a video of a Black man, chased down and shot like a dog in the street by two white men in a pickup truck in my own home state of Georgia.

I’ve seen another video, one that made this mama sob until my throat was raw, of another Black man crying meekly for his own mama as an officer’s knee to his neck cut off his breath, forever.

I’ve seen white people post black squares on Instagram, and then I’ve seen memes warning of the perils of performative allyship. I’ve seen comment section after comment section decrying racism and, then, accusations of “reverse racism” (not a thing).

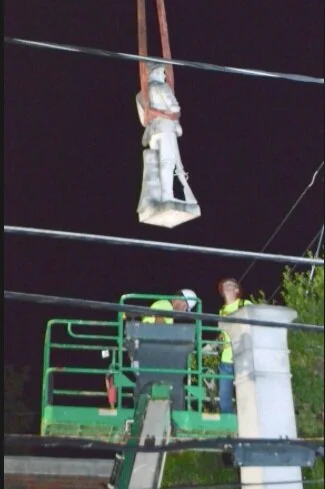

Hell, I’ve even seen what I never thought, but always hoped, I would: a statue glorifying Confederate soldiers in the center of my town brought down to a boom of applause tinged with boos.

I’ve seen finger pointing, eye rolling, what-aboutism, strawman arguments, defensiveness, denial.

What I haven’t seen much of — and what I often find lacking in today’s society — is genuine self-reflection and vulnerable honesty, specifically about how we as white individuals might have contributed to, or at least benefited from, the societal power structures that form the basis of systemic racism. It’s what we allies and anti-racists call “doing the work,” and I’m here to tell you, I’ve witnessed painfully little of it.

So, in the words of modern-day poets Rage Against the Machine, “What better place than here? What better time than now?”

My name’s Katy, and I’m a proud Southerner. I’m also a reluctant and recovering participant in what I call respectful racism.

If you’re from the South, y’all know respectful racism. It’s a slippery, hard-to-nail-down form of racism, typically trotted out by well-meaning yet unknowingly ignorant middle-to-high-class white people. But it’s racism nonetheless. Here’s what it sounds like:

“I’m not prejudiced… I just prefer to be around white people.”

“Everybody absolutely has equal rights. We just had a Black president!”

“I would never say the n-word. Only rednecks do that.”

“I don’t see color, and I wish everyone could just get along!”

“I hate that those people died, but looting? That’s just uncalled for.”

I’ve known it when I’ve seen and participated in it, so I absolutely believe people of color when they say they’ve encountered it. You’ll find no gaslighting here.

My experience with respectful racism started at birth. I was born into (adopted into, if you want to get technical) a wealthier middle-class white family in rural Middle Georgia. My family ran their own successful businesses, and my parents could afford to send me and my brother to a private preparatory school, which was nearly all white, for 14 years. We were known and respected in our small Main Street community, as were all of my close friends’ families. We were polite. We went to church. We volunteered. We gave money to causes. We helped folks when we could.

We were all good people. I was good people. But I was a little respectfully racist.

It’s not like I meant to be. It was a slow swell, starting with the general feeling of nostalgic Confederate reverence.

“It’s heritage, not hate!” we all repeated, gleaning our conviction from worn-out bumper stickers slapped on the ass ends of 70s-model Chevy trucks. It would take years before I realized it was in reality a heritage of hate.

It continued when I asked about Mr. Williams, a long-time customer and Black man in his 80s who would only pick up his to-go fried catfish plate at the back entrance of our restaurant.

“He just wants to go back to the days of segregation,” I was told. I know now that he was likely distrustful and potentially even scared of white people, and who could blame him, given the era he’d lived through during his formative years.

It reached its peak when I was a cheerleader in high school, and during a basketball game the opposite team’s student section chanted, “Oreo! Oreo!” — a nasty, albeit not outright foul, slur reserved for those deemed not-completely-white — at our team’s only mixed-race player.

We were all pissed, and felt righteous in our anger. We all thought it was wrong. We all felt for that kid… that kid. But nobody said anything, for fear of what my mother would’ve called “upsetting the apple cart.”

I didn’t say anything. After all, I wasn’t the racist one, I reasoned. In my young, naïve mind, there was no need to get involved with a problem that didn’t directly affect me. And didn’t the fact that I was upset by the incident prove I couldn’t possibly be complicit in his hurt?

“It starts with making a sincere effort to put oneself in the shoes of a Black person, without making the exercise about you in the process. ”

This brand of tacit racism lite is especially insidious because it allows the subject to truly believe they’re not capable of being racist, therefore absolving themselves of looking inward and asking the hard questions about their perceptions of the BIPOC community. In the minds of the respectful racists, “doing the work” is for the abject racists – the guy with the rebel flag tattooed on his neck (many respectful racists wouldn’t be caught dead with a tuh-TOO). The work is for the people hollering, “Oreo!”… right?

In reality, these are the exact people for whom the work could be the most impactful. They’re largely well educated, well intentioned and well regarded in their communities. In other words, they’re not lost causes. They could be brought to reason, and could be drivers of meaningful change in their white communities.

It starts with making a sincere effort to put oneself in the shoes of a Black person, without making the exercise about you in the process. This is tough for those struggling with respectful racism, because they’re typically already empathetic characters. In my case, the road to recovery from respectful racism began with a book. Specifically, Black Boy by Richard Wright, required reading for Mrs. Sweetapple’s AP American Literature class.

This gal would argue it should be required reading for life.

I’ll be real with you. To do this work, you have to get real cool real fast with a couple of things. First and foremost, you have to be cool with being wrong. At its heart, the work of dismantling systemic racism is humbling as a white person, and for prideful people who enjoy the respect of their communities, admitting you were wrong at any point in your life can feel unfathomable.

Secondly, you have to be cool with people — maybe even those you care about — speaking disparagingly about you. You’ll need to be prepared to be called any number of names from the Ignorant’s Thesaurus — snowflake, race traitor, white apologist, reverse racist (again… not a thing).

Just repeat after me: “That’s ok, Karen. I’ve been called worse things by better people.”

Here’s to the work. I’ll see y’all in the classroom.

By day, Katy is a brand marketing leader, while at home her husband and two sons, Wiley and Hill, call her “mama.” Hailing from middle Georgia, today Katy, in her free time, chairs a food insecurity non-profit. If you run into her at an Atlanta bar, she’ll take the Whistle Pig rye or the Loire Valley chenin blanc, thank you.